Review-First Programming

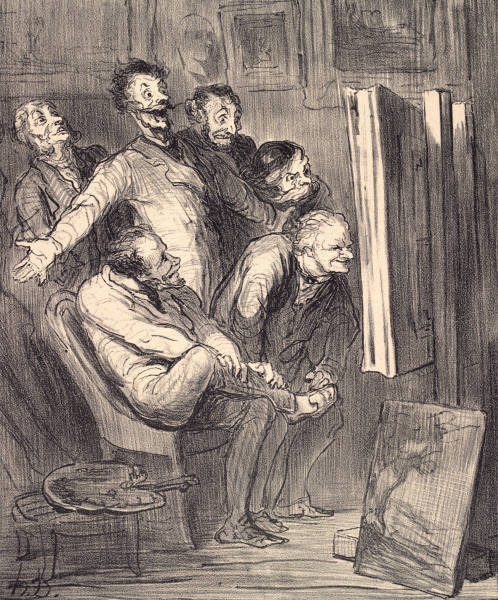

Art Criticism by H.Daumier

Food critics who can't cook at Michelin level. Editors who don't write novels. Casting directors who can't act.

Different skill. Not lesser skill.

LLMs are revealing something we've ignored: generation and evaluation are cognitively asymmetric. Research on utterance planning shows construction is harder than execution. Starting from nothing costs more cognitive load than refining something that exists.

This isn't new. "Real Programmers Don't Use Pascal" (1983) mocked structured programming as "quiche eating." Every abstraction faced resistance from people who valued control over leverage.

Review-first programming isn't decline. It's specialization.

The developers adapting fastest aren't the ones who generate the most code. They're the ones who know what not to build.

I've noticed something intriguing lately. When working with LLMs, more developers are finding that they are better at reviewing code than writing it. At first the statement sounds like an admission of incompetence. But what if it's not? Perhaps it's actually a recognition of how different cognitive skills work.

The Cognitive Architecture

It's hard to write code from scratch. You have to deal with syntax, design patterns, edge cases, and architecture all at the same time. It's like trying to hold multiple conversations simultaneously. Reviewing code is simpler. You look at what's there and ask one question: Does this solve the problem correctly? This explains what I've heard from a number of developers: they feel more capable reviewing LLM-generated code than writing their own.

Some worry this means they're becoming worse programmers. I don't think it's necessarily true. They're becoming different programmers.

Generation vs. Evaluation Asymmetry: There is a real and measurable difference between these skills. Writing code takes a lot of brainpower. When you review code, you can just focus on making sure it's correct. But this isn't a limitation; it's how human cognition actually works.

Research on language production shows that [utterance planning can be "more demanding than speaking itself." The construction of motor plans is a cognitively demanding activity. The significant computational difficulty of constructing and maintaining an utterance plan parallels what happens when writing code from scratch.

Studies on cognitive complexity demonstrate that processing relations between entities is more cognitively demanding than processing features of individual entities, and comparisons assessing difference are more complex than those assessing similarity. The asymmetry explains why evaluation feels easier than generation.

The generation effect in memory research shows that while self-generated information has memory benefits compared to read information, the strain during generation significantly affects cognitive load. This meta-analysis of 126 articles helps explain why starting from a blank slate is harder than evaluating existing solutions.

Recognizing Patterns Instead of Making Them: Humans are pretty good at knowing when something is wrong, even if they can't say right away what the right answer is. Food critics evaluate Michelin-star cuisine but can't cook at that level themselves. There are editors who specialize in refinement, seeing what works in existing text, rather than generation from nothing. Casting directors who identify perfect actors but can't perform the roles themselves.

The Blank Canvas Problem: Starting from scratch is cognitively expensive. Even developers with a lot of experience copy and paste their own code as scaffolding. LLMs provide infinite scaffolding. This lets you focus all of your energy on what really matters: correctness, architecture, and judgment.

Recent research confirms that LLMs reduce cognitive load through structured scaffolding strategies. The study shows LLMs serve as knowledge scaffolding, providing targeted instructional materials and working examples that help establish procedural rules in long-term memory. This reduces cognitive load while improving computational thinking.

The Biscuit research demonstrates how LLM-generated scaffolds help programmers understand, guide, and explore code. By offering UI-based scaffolds as an intermediate layer between natural language requests and code generation, these systems reduce the complexity of prompt engineering and create more efficient workflows for working with tutorials and unfamiliar code.

The Skill Transformation

It's not that the skill is less; it's just different. When you review LLM code, you're figuring out what the author meant by looking at the artifacts. You're reasoning from first principles. You're keeping the architectural coherence of parts you didn't write. This might actually need more knowledge than regular programming.

This parallels earlier shifts in programming. In 1983, Ed Post published 'Real Programmers Don't Use Pascal' in Datamation, contrasting assembly and FORTRAN programmers with 'quiche eaters' who used structured languages. Every new abstraction layer since has faced similar resistance from programmers who valued the control and performance of lower-level languages. Each generation was right in some way: something was being abstracted away. But the best programmers at each level knew how to work with the layer below regardless.

The developers who will have a hard time with this change are the ones who see themselves as creators rather than curators. But the best editors often understand deeper principles than the best writers. They just express that understanding differently, like through recognition instead of generation.

The Benefit of Scalability

There is also a practical benefit. A developer who is good at reviewing and directing can use more than one LLM at the same time. They can spin up different approaches, compare outputs, iterate faster. They are conductors rather than performers.

Tools for orchestrating multiple coding LLMs enable developers to leverage different models' strengths—using specialized models for different languages, frameworks, or problem types. This conductor model amplifies the review-first approach.

Research on hierarchical code generation shows that systems supporting multiple levels of abstraction—from high-level goals to specific implementations—help coders reduce cognitive switching between prompt authoring and code evaluation. Thus preventing disruptive context shifts and providing better control over translating intentions into bytes.

Could it be the case that programming that starts with a review works better than traditional development? The change from generation to evaluation changes what it means to be an expert.

LLMs generate perfect syntax but don't know when not to use it. They'll implement distributed systems when a single process would do. They'll create elegant abstractions that become maintenance nightmares. The expertise is knowing what not to build.

Pattern recognition over pattern generation...

LLMs invert the traditional constraint. Generation becomes cheap. Good judgment becomes scarce. This plays to human cognitive strengths in ways we're only beginning to understand.